Illegal pigeon hunting across Samoa is risking the extinction of the country’s national bird: the little dodo or manumea. Will this little-known island pigeon suffer the same fate as its namesake?

Nearly two hundred years after the extinction of the dodo, Sir William Jardin – a Scottish naturalist and bird-aficionado – described another odd, bulky, island pigeon. From the island of Samoa, this one was distinguished by a massive, curving bill that sported tooth-like serrations on its lower mandible. Given the strangeness of the creature, Jardine set it in its own genus and dubbed it Didunculus – the little dodo. Genetic evidence has since confirmed that the tooth-billed pigeon – or little dodo – is one of the closest living relatives of its long-deceased namesake. Today, the little dodo is at the very precipice of extinction, but it remains nearly as cryptic and little known as it did when Jardin gave it a scientific name in 1845.

The little dodo “is the last surviving species in its genus,” Rebecca Stirnemann said. “The Fijian and Tongan species [of the little dodo] are both extinct. It is the national bird of Samoa and appears in many of the stories often in association with chiefs.”

Stirnemann, a New Zealand biologist and conservationist, has spent the last eight years working in Samoa to safeguard the nearly extinct bird, which is known locally as the manumea.

Stirnemann, currently with conservation New Zealand NGO Forest and Bird, says there are three threats to the manumea or little dodo: destruction of forest on the island, invasive mammals (especially cats) and pigeon hunting. As to the latter, it’s not that local Samoans are hunting the little dodo itself, but in shooting the Pacific imperial and other pigeon species they sometimes kill the little dodo as “bycatch.”

“Action is urgently needed to stop [the pigeon hunting] if the manumea is not to be lost,” said Stirnemann, who recently detailed the crisis in a paper in Biodiversity and Conservation. The pigeon trade has been banned in Samoa since 1993, but is widely flouted.

Stirnemann saw her first manumea when she was working on conserving another local bird, the mao.

“It is a beautiful species with a giant red hooked beak,” Stirnemann said of the little dodo. “I have been hooked ever since.”

There are few quality photos of the species in existence. Often, it’s either a photo of a dead animal or a gloomy shot that makes the animal look almost vulture-like. In reality, the species is quite colorful: with a blue-gray head and breast and rufous-coloured wings. The genetic evidence shows that the little dodo was the first of its of its relatives to branch off, making it the most ancient of the dodo’s cousins. It’s so strange and rare, the Zoological Society of London’s Edge of Existence programme has placed the little dodo as number 16 pn their list of the 100 most evolutionary distinct and globally endangered birds.

Stirnemann and her team have conducted numerous surveys for the bird only to discover that it is even more at risk than first believed. The best estimate is that less than 250 birds survive; the real number could be considerably lower. However, conservationists got a piece of good news in 2013 when they were able to confirm the bird is still breeding.

“Our research to date shows that the lowland forests are critical for this species. Unfortunately that is also the area where most people live and where hunting pressure is the greatest,” Stirnemann said.

Conducting interviews with 30 hunters, the team found that nearly a third had accidentally killed more than one manumea during their career. Two birds were shot as recently as 2016.

Using a government database the scientists estimate that the illegal pigeon hunting trade on Samoa kills a staggering 22,000-33,000 pigeons a year.

“The government is currently undertaking a campaign to build awareness of the problem in the villages,” Stirnemann said. “They are doing a good job, but still more needs to be done if the manumea is to be saved. The consumers of pigeons are a really pig problem. If you are eating pigeon you are affecting the likelihood that manumea will continue to exist.”

The pigeon trade isn’t driven by hungry islanders looking for cheap meat, according to the scientist. Instead, pigeon proved to the most expensive meat on the island – nine times costlier than chicken.

“People often think that forest meat is consumed by poor people who have to hunt in the forest to survive,” Stirnemann said. “But across the world patterns…are emerging that rich people are driving wildlife trade. They are often unaware of the impacts they are having since they often do not enter the forest.”

According to the study the richest 10 percent of Samoans ate nearly half of the killed pigeons on the island. The total trade is worth less than £100,000.

Stirnemann said that an awareness campaign is needed to shift Samoan behavior before its too late.

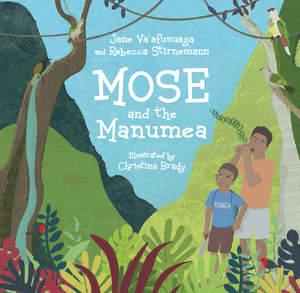

“The Samoan government and local NGOs are talking with villages to reduce hunting and to educate people. We are also producing a children’s book which will raise awareness of the issue and educate children to love the forest,” Stirnemann said. “My worry is that time is…running out for the manumea and hunting is still occurring.”

A number of organisations have been involved in little dodo conservation efforts including the Rufford Foundation, the Falease’ela Environment Protection Society (a local NGO), the Auckland Zoo, the Darwin Initiative and the Samoan government. But more funds and efforts from the international community are urgently required, according to Stirnemann, if the species is to be pulled back from the brink.

“There are many pressures on Samoa’s funding with the climate change crisis,” she said. “However, there are some amazing people in Samoa with the passion to save the forest and the native birds.”

The decline of the little dodo and of pigeons in general on the island – Stirnemann says that the Pacific imperial pigeon population has fallen dramatically in Samoa – is likely having a large impact on the diversity and health of the island’s forests.

“[The manumea] is an extremely important species in Samoa because it is a critical seed disperser or forest gardener,” Stirnemann said. “Other animals and birds cannot do the same job because they have smaller mouths and therefore eat smaller seeds. The large beak and mouth of the manumea allows it to feed and swallow large native trees seeds whole…replanting and maintaining the forest.”

It took only a century for humans – and the animals they brought with them – to wipe the dodo off Earth’s stage. Somehow, though it’s cousin – the little dodo, tooth-billed pigeon or manumea – has managed to live alongside humans for over three millennia. That may be about to change: without rapid, decisive action, the little dodo will very likely follow its cousin into oblivion. And humanity will have another species’ extinction hanging around our necks – our collective millstone.

“When you lose the manumea you lose the natural farmer of Samoa,” Stirnemann said.